How Did The Cold War Change The Preception Of Nuclear Power

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/e0/83e02b92-b91f-40f8-a05f-36cd040debf9/nuclearwinter-ratio.jpg)

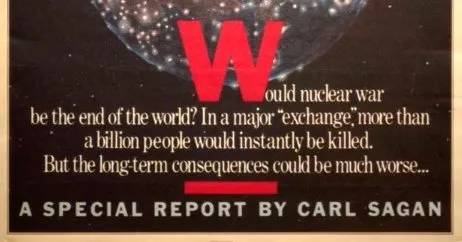

If yous were one of the more 10 1000000 Americans receiving Parade magazine on October 30, 1983, you would take been confronted with a harrowing scenario. The Sunday news supplement'due south front cover featured an prototype of the globe half-covered in gray shadows, dotted with white snow. Alongside this scene of devastation were the words: "Would nuclear war be the end of the world?"

This article marked the public's introduction to a concept that would drastically change the fence over nuclear war: "nuclear winter." The story detailed the previously unexpected consequences of nuclear state of war: prolonged dust and smoke, a precipitous drop in Earth'southward temperatures and widespread failure of crops, leading to deadly famine. "In a nuclear 'exchange,' more than a billion people would instantly be killed," read the comprehend. "Merely the long-term consequences could be much worse..."

According to the commodity, it wouldn't take both major nuclear powers firing all their weapons to create a nuclear winter. Even a smaller-scale state of war could destroy humanity as nosotros know it. "We have placed our civilization and our species in jeopardy," the writer concluded. "Fortunately, information technology is not yet too late. We can safeguard the planetary civilization and the man family unit if we so choose. At that place is no more than important or more urgent effect."

The article was frightening enough. Only it was the author who brought authority and seriousness to the doomsday scenario: Carl Sagan.

By 1983, Sagan was already popular and publicly visible in ways about scientists weren't. He was a charismatic spokesperson for scientific discipline, particularly the exploration of the solar system by robotic probes. He hosted and co-wrote the PBS television series "Cosmos," which became the most-watched science programme in history and fabricated him a household name. His 1977 book,The Dragons of Eden, won the Pulitzer Prize. He was well-known enough to be parodied past Johnny Carson on "The Tonight Show" and Berkeley Breathed in the "Flower County" comic strip.

Merely with his Parade article, he risked puncturing that hard-won popularity and brownie. In the fallout from the article, he faced a barrage of criticism—non simply from pro-nuclear conservatives, simply besides from scientists who resented him for leveraging his personal fame for advancement. Sagan later chosen discussion surrounding nuclear wintertime following the commodity "perhaps the most controversial scientific debate I've been involved in." That might exist an understatement.

And so the question is: What was a scientist doing getting involved in politics and writing most nuclear war in the pop presses in the beginning place?

.....

The nuclear winter chapter of history began in the tardily 1970s, when a group of scientists—including Sagan—entered the nuclear arms fray. These weren't nuclear physicists or weapons experts: they studied the atmospheres of World and other planets, including dust storms on Mars and clouds on Venus.

In 1980, paleontologist Luis Alvarez and his physicist begetter Walter presented evidence that an asteroid had hit Earth at the terminate of the Cretaceous Menstruum. They argued that the impact had thrown so much dust and debris into the air that World was blanketed in shadow for an extended period, long enough to wipe out the final of the non-bird dinosaurs. If true, this hypothesis showed a way that a catastrophe in one location could have long-term effects on the entire planet.

Sagan and his former students James Pollack and Brian Toon realized this piece of work applied to climate change on Earth—as well every bit nuclear state of war. Along with meteorologists Tom Ackerman and Rich Turco, they used computer models and information collected by satellites and space probes to conclude that it wouldn't accept a full-scale thermonuclear state of war to cause Earth's temperature to plummet. They found average global temperatures could driblet between 15º and 25º Celsius, plenty to plunge the planet into what they chosen "nuclear winter"—a deadly period of darkness, famine, toxic gases and subzero cold.

The authors best-selling the limitations of their model, including poor predictions for short-term effects on small-scale geographical scales and the inability to predict changes in weather every bit opposed to climate. However, their decision was chilling. If the U.s.a. managed to disable the Soviet arsenal and launch its own preemptive nuclear strike (or vice versa), they wrote, the whole earth would endure the consequences:

When combined with the prompt destruction from nuclear smash, fires, and fallout and the later enhancement of solar ultraviolet radiation due to ozone depletion, long-term exposure to common cold, dark, and radioactive decay could pose a serious threat to human survivors and to other species … The possibility of the extinction of Man sapiens cannot exist excluded.

The nuclear winter newspaper was accepted for publication in the journal Science , where information technology was destined to reach millions of scientists and influence decades of hereafter research. Known colloquially by the acronym "TTAPS" later its authors' final names, the academic article would be published on December 23, 1983. But in October, Sagan made the decision to denote his warning to the globe using what amounted to a very unorthodox medium: the popular media.

…..

Sagan, similar many at the time, believed nuclear war was the single greatest threat facing humanity. Others—including policymakers in the Reagan administration—believed a nuclear war was winnable, or at least survivable. Making the danger of nuclear winter real to them, Sagan believed, would take more than scientific discipline. He would have to draw on both his public fame, media savvy and scientific authority to bring the what he saw equally the truthful risk earlier the optics of the public.

That meant a rearranging of personal priorities. According to his biographer, Keay Davidson, at a meeting in the early on 1980s to plan theGalileo space probe, Sagan told his colleagues: "I take to tell you I'thou non probable to practise much of anything onGalileofor the adjacent yr or and then, because I am concentrating most of my energies on saving the world from nuclear holocaust."

According to Grinspoon, whose father, Lester, was a close friend of Sagan's and who knew all the authors (Pollack was his postdoctoral advisor), Sagan wasn't a major scientific contributor to the TTAPS paper, though he was intimately familiar with the research it contained. Nevertheless, the collaboration needed his high public profile to navigate the inevitable public controversy to come, in part considering NASA was worried about political retaliation that might rebound on funding, Grinspoon writes in his bookEarth in Homo Easily.

Toon, Ackerman and Pollack all worked at the NASA Ames Enquiry Center. Equally Davidson notes, "Ames director Clarence A. Syvertson … was also apparently terrified of doing annihilation to antagonize the Reagan Administration." So Pollack called up Sagan, who intervened and got Syvertson to drop his objections.

Though his role in TTAPS was largely greasing the wheels, Sagan'due south prominence andParade slice meant the public tended to associate nuclear winter with him lonely. As Davidson's biography notes, Sagan was the one invited to debate nuclear wintertime before Congress in 1984. He was later invited by Pope John Paul Ii to discuss nuclear winter. And in 1988, he was mentioned by Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev in his coming together with Reagan equally a major influence on catastrophe proliferation.

That meant people'southward personal feelings about Sagan colored their assessment of TTAPS. Unfortunately, it wasn't hard to attack such an outspoken messenger. As historian of science Lawrence Badash writes inA Nuclear Winter's Tale: "The columnist William F. Buckley Jr. said Sagan was 'so arrogant he might have been confused with, well, me.' He was faulted for strutting around on the Telly screen, conveying an uncomfortable paradigm for almost scientists, ane to which they had difficulty relating."

…..

Of grade, Sagan was inappreciably the first or last scientist to use his public fame for advocacy, nor to face criticism for it. Scientists who have stepped into the public heart include Marie Curie, Linus Pauling and Freeman Dyson; celebrity physicist Albert Einstein used his platform to decry American racism.

These figures are often seen alternatively equally either noble, fearless explorers bound to discover the truth, no matter how challenging—or stooges of the establishment, easily bought off with government and industrial coin, compromising their research.The reason for the contradictions is straightforward: scientists are people, and every bit such hold a variety of political opinions.

Merely the Cold State of war in particular threw those differences into stark contrast. Though his inquiry credentials were impeccable, Carl Sagan was in many ways a Common cold War warrior'south stereotype of a hippie scientist. He wore his hair long by conservative bookish standards, dressed modishly and casually, and was an outspoken critic of nuclear proliferation. (He likewisesmoked marijuana, which probable would have made his more direct-laced critics flip out if that fact had been widely known.)

He even helped write the nuclear arms-control section of President Carter'south bye address, using phrases familiar fromCosmos and his other writings."Nuclear weapons are an expression of 1 side of our homo character," Saganwrote. "Only in that location'due south another side. The same rocket technology that delivers nuclear warheads has likewise taken u.s.a. peacefully into infinite. From that perspective, we run across our Earth as it actually is—a modest and fragile and beautiful blue world, the simply home nosotros take. We see no barriers of race or religion or country. We come across the essential unity of our species and our planet. And with faith and common sense, that vivid vision will ultimately prevail."

On the other side of the spectrum were scientists like physicist Edward Teller, whose anti-Communist zeal was especially notable. He pushed for the U.Due south. to increase weapons research, and believed the United states of americaS.R. was a more powerful adversary than American intelligence agencies were reporting. Teller oft took existing threat analyses and extrapolated them into worst-instance scenarios in the interests of spurring the government toward more aggressive action. He strongly opposed nuclear test bans and believed the Soviets were shut to beginning a total-calibration nuclear state of war.

Teller supported the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a system of anti-nuclear satellites colloquially known every bit "Star Wars." Many analysts opposed SDI considering it would potentially escalate the arms race; in 1986, 6,500 scientists pledged their opposition to SDI in part because they doubted it would work at all.

Nuclear winter pitted Sagan against Teller, culminating in both men giving testimony before the U.S. Congress. Teller took personal offense at the conclusions of TTAPS: if the nuclear winter hypothesis was right, SDI and other strategies Teller promoted were doomed from the kickoff. It didn't hurt that their tactics were similar: in public statements, Sagan focused on the nearly farthermost predictions for nuclear winter, just as Teller cherry-picked information to exaggerate the Soviet threat.

…..

Sagan'southward deportment drew a personal backlash that reverberates into the nowadays—near notably, in the realm of climate modify.

At the fourth dimension, many of Sagan's opponents were strong supporters of SDI, which has been unsuccessfully re-proposed multiple times since. "Carl Sagan and his colleagues threw a [wrench] in the works, arguing that any exchange of nuclear weapons—even a modest ane—could plunge the Earth into a deep freeze," write Naomi Oreskes and Erik 1000. Conway in their volume Merchants of Doubt . "The SDI lobby decided to attack the messenger, kickoff attacking Sagan himself, so attacking scientific discipline mostly."

Like tactics were used confronting environmental scientist Rachel Carson, Oreskes and Conway betoken out. Long afterwards her death, anti-environmentalists and pro-DDT activists proceed to focus on Carson the person rather than the research done by many scientists across disciplines, as though she alone ended the indiscriminate use of that insecticide.

In the case of nuclear winter, the consequences of this backlash would be profound. In 1984, a pocket-size grouping of hawkish physicists and astronomers formed the George C. Marshall Institute, a conservative think-tank that supported SDI.

Their leader was Robert Jastrow, a bestselling author and occasional Television receiver personality whose politics were nearly contrary Sagan'due south. The Marshall Establish's tactics largely involved pressuring media outlets into "balancing" pieces critical of SDI with pro-"Star Wars" opinions. The Marshall Plant—and its successor the CO2 Coalition—later applied those same tactics to the result of climatic change. A former director of the establish, physicist William Happer, is a prominent climate-modify denier who has consulted with President Trump.

Climate scientists accept been hurt by these tactics, to the point where they often emphasize the best-case scenarios of climate change, as climate scientist Michael E. Mann writes in his bookThe Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars. Others, however, are concerned that downplaying the crunch makes it sound like we don't have to worry as much. Like Sagan, many researchers want to outcome a straight call to activity, even at the risk of being labeled a scientific Cassandra.

Comparing 1983 with 2017, the best word Grinspoon can recollect of is "deprival": "People didn't want to alter the manner they were thinking of [nuclear] weapons," he says. "I see an echo of that now. What nuclear winter shows is that they're not really weapons in the sense that other things are weapons: that y'all can use them to harm your antagonist without harming yourself. People are non really considering that if there really were to exist a nuclear conflagration, in add-on to how unthinkably horrible it would be in the direct theater of the use of those weapons—say in the Korean peninsula and surrounding areas—at that place would too be global furnishings."

…..

Today we alive in a vastly different earth. Global nuclear weapons number around ane-fourth of what they were in the '80s, according toThe New York Times. And the threat of global thermonuclear war has mostly faded: Few believe that N Korea's potential armory is capable of wiping out American cities and nuclear silos the mode the former Soviet Spousal relationship could.

Merely that doesn't mean the legacy of TTAPS and Sagan is dead. The nuclear winter hypothesis could mean even a smaller nuclear war such as 1 fought between the U.S. and North korea would harm the globe for years to come. Thus, nuclear wintertime is still an important area of research, forming much of TTAPS writer Brian Toon's subsequent enquiry. Lately he and collaborators accept focused on the consequences of hypothetical smaller-theater wars, such one betwixt India and Pakistan, or betwixt North Korea and the U.South.

The fence over climatic change isn't going away someday before long, either. And the way Sagan and his scientific colleagues handled publicizing and debating the nuclear wintertime question seems very similar to those tracking climatic change. In both instances, the potential impact of the scientific discipline is huge, with implications beyond the scope of the research, and valid concerns about either understating or overstating the risks.

"Both nuclear winter and global climatic change are fairly abstruse phenomena that occur on a scale beyond our immediate sensory experience," says Grinspoon. "We're asking people to take a outcome and imagine a change that is just beyond the realm of any of united states, what we've experienced in our lives. That's something man beings aren't peachy at!"

That means that the debates will go along. And whenever there are scientific issues that spill over into human affairs, like issues will crop up. After all, scientists are humans, who intendance about politics and all the other messy matters of life. In his 1994 volume Pale Bluish Dot , Sagan wrote upon seeing an image of Earth from Voyager 1, "To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the stake blueish dot, the only domicile we've always known."

How Did The Cold War Change The Preception Of Nuclear Power,

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/when-carl-sagan-warned-world-about-nuclear-winter-180967198/

Posted by: holtvared1955.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did The Cold War Change The Preception Of Nuclear Power"

Post a Comment